As a female coach and ex professional triathlete, I had the opportunity over the years to study myself and my coached female athletes, how our body reacts to training and racing in different phases of the menstrual cycle, different training loads and nutritional needs. Therefore we can make our training unique for us and use the right opportunity windows for specific types of workouts and also tailor our nutrition around our menstrual cycle. For this we need to understand a little about the physiology behind this. Here is a brief intro into the differences in the physiological systems between males and females.

Scientific literature has thrown light on the difference in physiological systems' response to exercise in males and females

- – Musculoskeletal system

- – Cardiovascular system

- – Respiratory system

- – Nervous system

- – Hormonal system

Musculoskeletal system

The proportional fibre-type difference between sexes also influences the contractile properties of skeletal muscle in males and females. It was demonstrated by research that the greater fatigue resistance of female muscle during exercise is related to the differences in ionic regulation. Evidence from muscle biopsies demonstrates a higher density of capillaries per unit of skeletal muscle in females compared with males in the vastus lateralis. Greater capillarisation, mitochondrial respiratory capacity and fatigue resistance.

Cardiovascular system

Womens VO2max is lower and is one of the factors limiting female performance compared to males. Female VO2max is 70-75% of the average male. Oxygen carrying capacity is also lower in females. The haemoglobin level is 10-14% below the average male and as well as blood volume, but the vasodilatory responses of the feed arteries to exercising skeletal muscles are greater in females and the density of the capillaries per unit of skeletal muscle.

Respiratory system

There are also anatomical and functional differences in males and females in the respiratory system. Women have smaller lungs, airways, and different lung geometry. These factors can influence respiratory efficiency and susceptibility to arterial hypoxemia. It's also one of the factors that are related to performance, especially at altitude, that needs to be considered when planning an altitude training camp. Women can’t handle the same training demands at altitude as men (in comparison to sea level). This factor also influences the VO2max that I already mentioned above - it is usually lower by around 15% in females.

Hormonal system

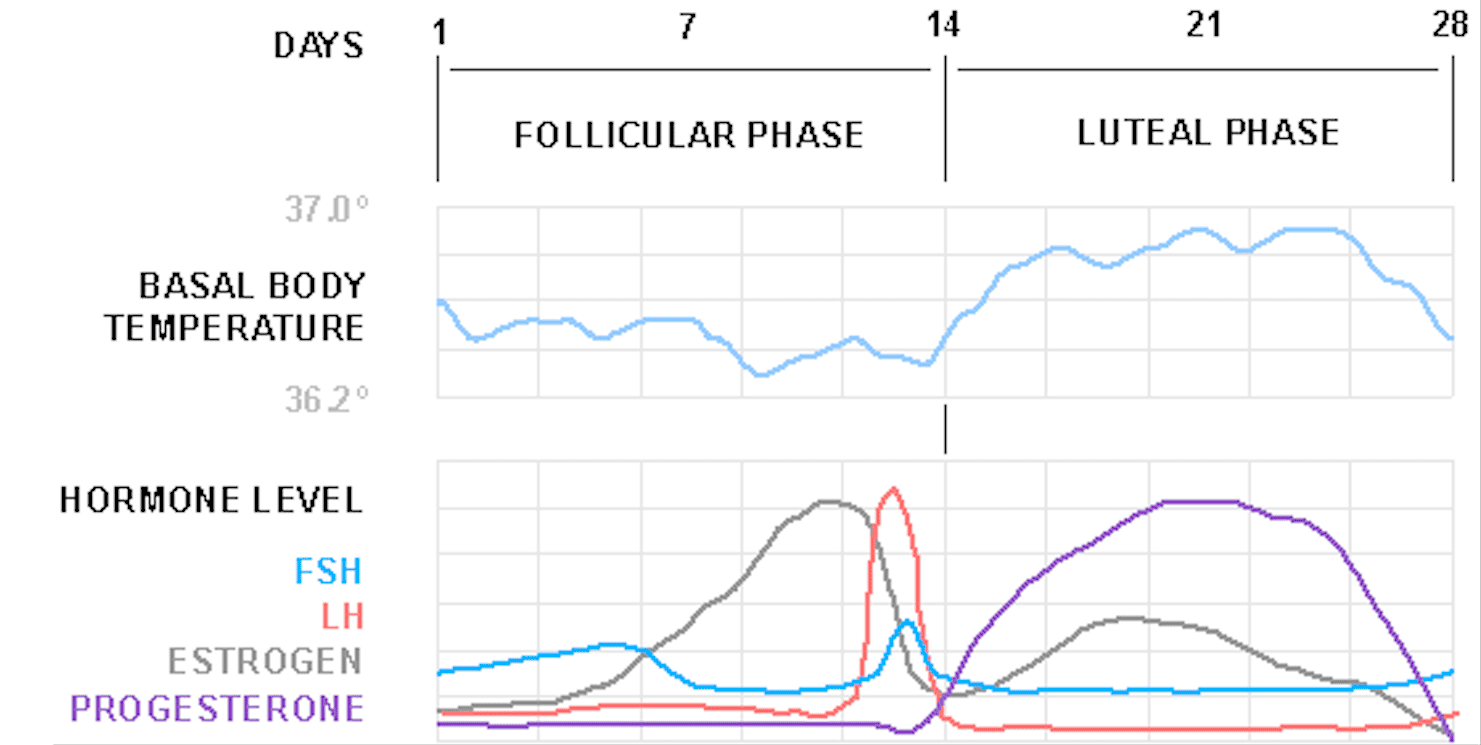

One average menstrual cycle is 28 days but there are individual variations from female to female and also how women perceive training during the cycle. During every menstrual cycle the follicular (early and late), ovulation and the luteal (early, mid-, late) phase takes place.

During the early follicular phase which typically lasts 3-7 days, low oestrogen and progesterone levels are reported. The late follicular phase is characterized by the increase of oestrogen and low progesterone. This period typically lasts for 16 days and continues until ovulation. The ovulation phase typically lasts 3-4 days. This is the phase when ovulation occurs. After the ovulation phase, the luteal phase begins when there is a rise in progesterone and a slight increase of oestrogen, followed by a drop in both hormones at the late luteal phase. This is the moment when females can experience premenstrual syndrome and training needs to be adapted. This time is also known for feelings of bloating and water retention and sometimes fluctuation in body weight by +- 1kg extra.

After this phase, the cycle starts from the beginning. Is very important to have in mind the inter-individual variation of the different phases of the menstrual cycle and the symptoms can vary from person to person as mentioned earlier. It's very practical for female athletes and their coaches to keep notes in a training diary about the cycle and its different phases, for further analyses of performance and possible adaptations to training. You can also plan important races around your cycle if you belong among women who are more sensitive to hormonal changes.

Menstrual cycle phases

Throughout the menstrual cycle (MC) three distinct hormonal environments can be identified; the early follicular (EF) phase, characterized by low oestrogen and progesterone, the late follicular (LF) phase, characterized by high oestrogen and low progesterone, and the mid-luteal (ML) phase, characterized by high oestrogen and progesterone (Figure 1). A fourth phase may be considered and it is the ovulation one, that takes place in the middle of the entire menstrual cycle and in this phase, body temperature typically increases. This is something to monitor and pay attention to if you are planning racing at this time of the month in a hot climate.

Menstrual cycle graph

- – Day 1 of the cycle begins with the onset of menses (days 1-4) when both oestrogen and progesterone levels are low.

- – Day 14 is ovulation.

When a coach notices that an athlete is sensitive to menstrual phases' oscillations in training, they should make changes in the programme as this is a fundamental parameter of individualized training planning. A good tip is to use the RPE scale for training or giving a wider range for training zones to avoid overtraining.

Periodization of strength training

Two recent articles have studied periodization of strength training with varying frequencies during the different phases of the menstrual cycle.

In the first study (Wikström-Frisén, 2017), a significant increase in muscle strength and power was seen in the group with high-frequency strength training during the first two weeks of the menstrual cycle (EF).

Similarly, Sung et al. (2014) found significant differences between higher frequency strength training in the EF versus the ML phase. The EF phase was more beneficial to increase muscle strength.

Psychological effects

After many years of research, and also through my own experiences, I can confirm the negative effects of the premenstrual phase, where it is believed that 95% of women have negative emotions. We can feel less productive, less attractive or moody at times.

Also, during the mid cycle and just before ovulation, the level of oestrogen reaches its highest level, which makes for the highest levels of self-esteem and well-being during this time.

It‘s also worth noting that women's mental toughness is just as crucial in endurance sports as physical fitness. And here, we women have consistently demonstrated remarkable mental resilience in endurance/ultra-endurance sports. My female athletes don’t stop amazing me with their resilience and mental toughness on a daily basis.

Heat effects

A parameter that possibly can affect endurance performance negatively, especially in the week prior to the mid-Luteal phase is heat. During this phase, the body temperature is increased and might be a limiting factor for performance during the ML phase. This consideration needs to be taken for women who are performing endurance activities in heat, and a recommendation might be to plan competitions according to the menstrual cycle to avoid a negatively affected performance.

Recovery during different menstrual phases

There is some evidence that when oestrogen is high around the late Follicular phase (around ovulation), there is an increased risk of injury, because the hormone makes ligaments and tendons more lax.

Nutritional Needs

Women have different nutritional needs to men. Besides regular vitamins supplementations, there is a particular need for higher iron and calcium intake. Iron is vital for oxygen transport in blood and calcium is essential for bone health.

A stronger need for carbohydrate intake has also been discovered in the mid and late luteal phase (pre-menstrual), which also relates to body water retention. This is normal - if your body asks you for more carbs, or a treat, just give your body what it needs.

Body Composition

Women typically have a higher percentage of body fat than men, and so we should. It is crucial for us to maintain a certain percentage of body fat to retain regular menstrual cycles, immunity and long-term improvement. Body weight loss might create short-term improvement, but long-term it‘s very dangerous for overtraining, possible stress fractures or other types of injuries and loss of power and overall fitness.

Fat serves as a valuable energy source during prolonged exercise and women can tap into this resource effectively. I always prefer coaching athletes with more fat reserves than skinny ones prone to burn out or possible injuries.

Conclusion

In conclusion, women can and do excel in endurance sports, despite the physiological differences between the sexes. Understanding these differences and adapting training and nutrition strategies accordingly can help female athletes reach their full potential. Women's physiology in endurance sports is a complex and fascinating topic, and ongoing research continues to provide insights into optimizing performance and promoting the well-being of female athletes in this demanding field.

Author

REFERENCES

- Chidi-Ogbolu N, Baar K. Effect of Estrogen on Musculoskeletal Performance and Injury Risk. Front Physiol. 2019;9:1834. Published 2019 Jan 15. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.01834

- Elliot-Sale, K.S. (2014). The relationship between oestrogen and muscle strength: a current perspective. The Brazilian Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 28(2), pp. 339-349.

- Enns DL, Tiidus PM. The influence of estrogen on skeletal muscle: sex matters. Sports Med. 2010 Jan 1;40(1):41-58.

- Farage, M. A., Osborn, T. W. & MacLean, A. B. (2008) Cognitive, sensory, and emotional changes associated with the menstrual cycle: a review. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 278(4), pp. 299-307.

- Janse de Jonge, X.A.K. (2003). Effects of the Menstrual Cycle on Exercise Performance. Sports Medicine, 33(11), pp. 833-851.

- Kenney, W.L., Wilmore, J. H. & Costill, D.L. (2012). Physiology of Sport and Exercise, Fifth edition. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Middelton, L.E., & Wenger H.A. (2006). Effects of menstrual phase on performance and recovery in intense intermittent activity. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 96(1), p. 53–58.

- Oosthuyse, T. & Bosch, A.N. (2010). The Effect of the Menstrual Cycle on Exercise Metabolism: Implications for Exercise Performance in Eumenorrhoeic Women. (2010). Sports Medicine, 40(3), pp. 207-227.

- Sherwin, B.B. (2003) Estrogen and Cognitive Functioning in Women. Endocrine Reviews, 24(2), pp. 133-151.

- Smekal, G., Von Duvillard, S.P., Frigo, P., Tegelhofer, T., Pokan, R., Hoffman, P., Tschan, H., Baron, R., Wonisch, M., Renezeder, K. & Bachl, N. (2007). Menstrual Cycle: No Effect on Exercise Cardiorespiratory Variables or Blood Lactate Concentration. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 39(7), pp. 1098-1106.

- Sunderland, C., & Nevill, M. (2003). Effect of the menstrual cycle on performance of intermittent, high- intensity shuttle running in hot environment. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 88(4-5), pp. 345–352.

- Sung, E., Han, A., Hinrichs, T., Vorgerd, M., Manchado, C. & Platen, P. (2014). Effects of follicular versus luteal phase-based strength training in young women. Springerplus, 3(668), pp. 1-10.

- Tsampoukos, A., Peckham, E.A., James, R., & Nevill, M.E. (2010). Effect of menstrual cycle phase on sprinting performance. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 109(4), pp. 659– 667.

- Wikström-Frisén, L., Boraxbekk, C.-J. & Henriksson-Larsén, K. (2017). Effects on power, strength and lean body mass of menstrual/oral contraceptive cycle based resistance training. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 57(1-2), pp. 43-52

- McNulty, K. L. et al. The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Exercise Performance in Eumenorrheic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 50, 1813–1827 (2020).

- Kenney, W. L., Wilmore, J. & Costill, D. Physiology of Sport and Exercise 7th Edition With Web Study Guide. 648 (Human Kinetics, Inc., 2019).